Winter is a Time Loop

Haven't we been here before?

The cinnamon glow of the holidays has gone cold with distance. We’ve passed winter’s halfway mark but picnics and wildflowers still feel impossibly far ahead. Morning snow dissolves into afternoon slush, then freezes into sheets of ice after dark. I run on the treadmill to escape the slippery world. Its belt turns and turns under me while I stay still. When I leave the gym, I tunnel gingerly along the desire paths that connect the nodes of my city in the frost. It feels like living the same day over and over again.

Winter’s mood-dampening quality is usually explained by the lack of light, but I think low temperatures also have a blunting effect. Cold literally slows down time. My inner worldview takes cues from the punishing outer landscape: I crave my comfort zone, life crawling within familiar boundaries.

I recently read the first installments of Danish writer Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume, a hypnotic literary time loop saga. I had started to see the stylishly blobby covers of these books (reminiscent of aura photos) everywhere in certain literary scenes when they suddenly appeared inside my apartment. My boyfriend had reserved them months earlier at the library, and I piggybacked on his good taste by reading Books I and II before he returned them. On the Calculation of Volume follows an antiquarian bookseller named Tara Selter who travels to Paris on business and discovers over an unsettling hotel breakfast that she is living the same day twice. The people around her are following their same routines like automatons, their memories wiped of the previous day. The papers reset to yesterday’s news, the weather follows the same minute-by-minute patterns as the day before. She waits it out until nightfall, but the next morning it happens again. Again. Again.

Tara returns to the house in the French countryside that she shares with her husband, who becomes her patient but forgetful confidante. Every morning he is shocked to see her return “early” from her trip, and she must reexplain that she’s stuck in the time loop. Thankfully, he always believes her— which reminds me of stories I’ve heard about of real-life amnesiacs, whose responses often follow consistent patterns as stimuli are forgotten and re-encountered. Tara embarks on an uncertain, heartbreaking quest to restore time to its normal course. The date is (always) November 18.

On the Calculation of Volume is, I delight to inform you, so engaging that it feels almost interactive. We learn more about the physics of Tara’s new reality through her experiments and observations as she pushes the boundaries of her world’s un/natural order. The book is structured as a sort of captain’s log, building emotional valence and tension as the days layer up. Usually, November 18 is her prison, but it can also be her playground—she eventually begins to wander the earth, seeking the best way of life within the strange hand she’s been dealt. Ryan and I devoured Books I and II side by side, producing the uncanny experience of being out of sync within Tara’s loop together. Now the Danish-English translation lag forces us to wait for Books III-VII.

What makes this story so compelling? On the Calculation of Volume is an effective metaphor for depression; simulating its hallmark feelings of isolation, stagnation, and powerlessness; but there’s also something about a time loop that is perversely attractive. As we age, our relationship with time complicates. We make commitments and grapple with the limiting nature of choosing one path. We prepare for the irreversible deaths of the people who raised us, then for our own. We stew in an emphatically anti-aging consumer landscape, perhaps channeling our anxiety about our deteriorating planet into the pursuit of eternal youth. And of course, there’s capitalist burnout: despite the obvious horror of Tara’s situation, I found myself envying the endlessly replenishing bank account that allows her to rest, contemplate, forget her job and travel the world.

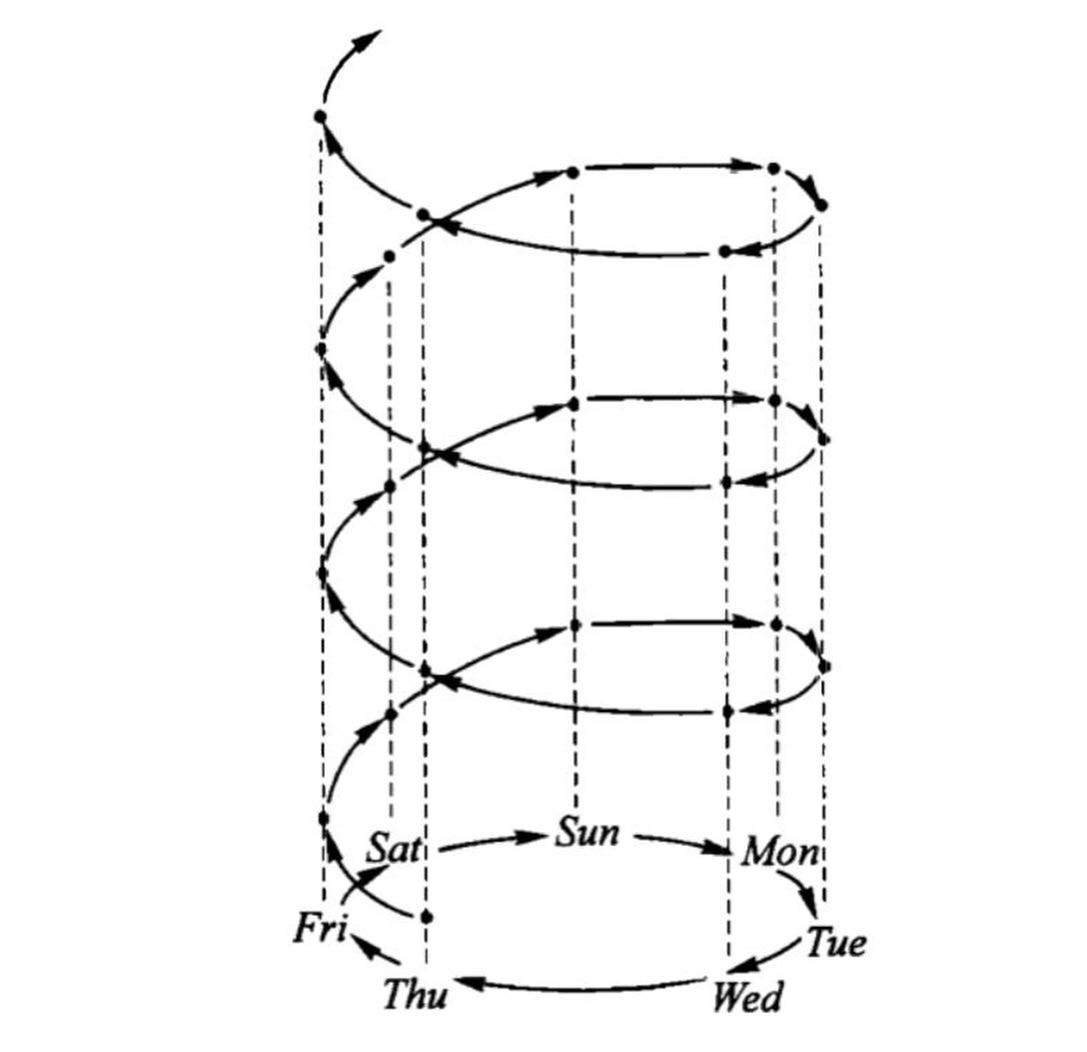

The Criterion Channel, also near and dear to my heart this winter, released a collection of films in December called Déjà Vu? featuring “looping timelines, fragmented memories, and alternate ‘butterfly effect’ versions of events.” They included Memento, Vertigo, Donnie Darko, La Jetée, etc. I was surprised by how many I had seen—do I have a predisposition to loopiness? Many of the themes that have fascinated me and defined my twenties are also characteristics of the time loop: finding my set point between the poles of spontaneity and structure, trying to generate novelty within the sameness of a simple life, the enchanting differences that emerge from the repetitions of a ritual. Cycles are a perennial obsession—friends have noted that all of my poems seem to be about washing dishes and watching seasons change.

Of course, it’s also possible that loopiness has a universal appeal and produces an outsize number of popular movies. A few months ago I watched Déjà Vu? selection Run Lola Run in a crowded theater that embraced it with clapping, cheering zeal. Our hero Lola, a young German woman, has twenty minutes to somehow acquire 100,000 Deutsche Mark (I think that’s roughly $90,000 USD today) and run it across Berlin to her boyfriend Manni after his delivery to a gangster goes wrong. When she reaches Manni and the dramatic finale plays out, we blink and suddenly find ourselves back at the start, like Lola has failed a level in a video game and must take it again from the top. Time loops, of course, have variations in mood: Donnie Darko is an eerie dream, Memento a taut puzzle, On the Calculation of Volume an existential laboratory. But I love Run Lola Run for its decidedly different flavor, more manic than depressive. Its tight twenty-minute loop span goes down like an espresso shot. I think of Franka Potente’s impressive physical acting as Lola on my interminable winter treadmill slogs: her energy seems to reset with each iteration, drawing from a deep well that exists beyond time.

Is winter the season of the time loop? Maybe there’s a reason its most famous example, Groundhog Day, takes place on the titular holiday. Everyone wears winter clothes in Russian Doll, Tara struggles with perpetual November in On the Calculation of Volume, Wikipedia’s list of time loop movies has a notable Christmas bias. A recent exception would be Palm Springs, starring Andy Samberg and Cristin Milioti, which unfolds at a balmy resort wedding. Palm Springs was one of those strangely prescient pandemic media phenomena that rolled out on streaming in the summer of 2020, when I was living in Brooklyn in a top-floor walkup with no air conditioning. I nailed blankets over the windows to keep the sun out and left only to buy groceries. After New York greenlit alcohol for takeout, a man from the restaurant outside would stand under my window and yell “Sangria, seven dollars!” for hours on end. I was unemployed, languishing inside a facsimile of leisure with global terror simmering underneath. The characters onscreen played out their parallel struggle, amidst the marital festivities, to find a way out of their time loop à deux.

Did time ever re-rail properly after that? Even now my age feels sort of wrong, like I’m older on paper than I am in real life, and my attention span has taken years to unwrench from the era’s warping effect. In retrospect, despite how constantly sweaty I was, that summer had a locked-in quality of spiritual winter. Solvej Balle is rumored to have secluded herself on a Danish island for decades to write On the Calculation of Volume. Huge if true— it sounds like the Palm Springs experience x 1000.

There’s an art to living in a time loop. You can bend your life around it, discover its exact contours. Tara Selter amazes her husband with her ability to predict the movements of birds, then uses the same trick to memorize his schedule and live secretly in her own guest room. You can also embrace the time loop’s possibility, the chance to shatter your reality and start over again. Lola does this, flying like a phoenix with her blazing red hair.

As for me, I’m trying to find glamour in bare faces, messy braids shoved into the backs of coats, chapped lips and hands. I have amassed a time loop survival kit: baths, teas, candles, a moon-faced “happy lamp”, The Beach Boys stubbornly blasting in my headphones while the wind lashes my face. And of course, I can take comfort in the fact that the calendar is literally progressing forward. Over the phone, an old friend wished me luck making it through the rest of winter— in my memory, they actually said “making it through the eye of the needle.” Another melt and freeze, another entry in the captain’s log. The eye of a needle, a tiny silver loop.